Bonne fête à mon papa qui n’est plus là et à tous les papas

Bonne fête à mon papa qui n’est plus là et à tous les papas

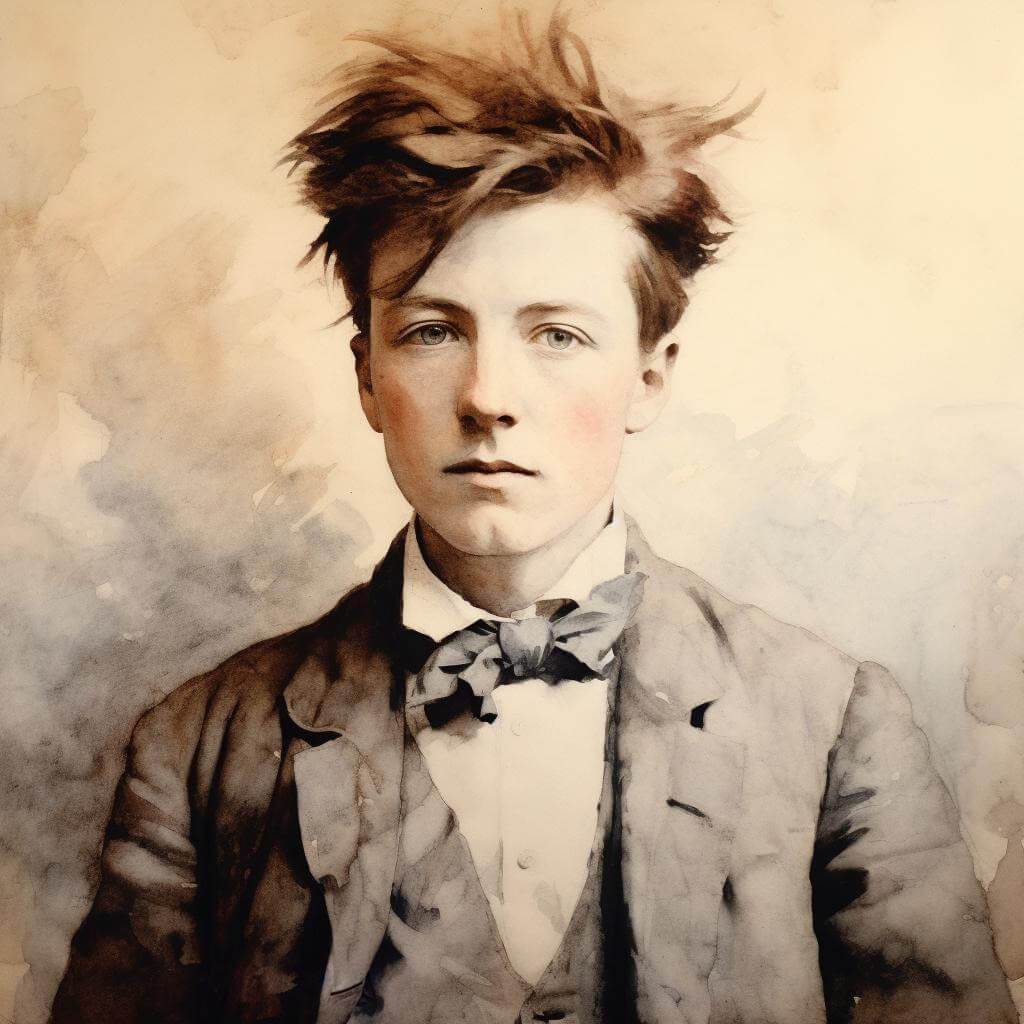

"No one's serious at seventeen.

On beautiful nights when beer and lemonade

And loud, blinding cafés are the last thing you need

You stroll beneath green lindens on the promenade.

Lindens smell fine on fine June nights!

Sometimes the air is so sweet that you close your eyes;

The wind brings sounds, the town is near—

And carries scents of vineyards and beer". . ."

- Arthur Rimbaud (20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891)

Birds on a Wire is an enchanting voice and cello duo formed by French-American singer Rosemary Standley (with multinational France-based alt-folk band Moriarty) and young Brazilian singer, songwriter and cellist Dominique Pinto aka Dom la Nena. Initiated by Rosemary Standley in 2011 as “Rosemary’s Songbook”, the project evolved into the Birds on a Wire duo when the producer of Madamelune – an independent Paris-based stage and music production company – introduced her to Dom La Nena. Touring as a live show in intimate venues from September 2012 onwards, the duo eventually went into a studio to record the songs.

Without adhering to any particular theme (love songs maybe?), focusing on a specific era or genre, Birds on a Wire is a stunning compilation of stripped-down ballads and lullabies selected by the two musicians with the cello lending a superb and consistent baroque feel to the collection.

Borrowing from the traditional, modern folk or baroque repertoires from the United States, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Lebanon, England or Italy, covering baroque composer Stefano Landi, John Lennon or Caetano Veloso, singing in Arabic, English, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese or French creole, Rosemary Standley and Dom la Nena have assembled a wonderfully eclectic, minimalist and timeless songbook.

Apart from the sparse addition of bells, recorders or drums on a few songs, the cello and voice combination remains central and generates the most subtle musical alchemy throughout the album. Dom la Nena also contributes vocally to a few songs (including her own “Sambinha” from her 2013 début Ela) and her use of the melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and even percussive possibilities of the cello literally turn the instrument into a “third voice”.

The duo revisits Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the wire” of course or “Blessed is the memory” which originally appeared as a bonus track on the 2007 reissue of Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967). The reprise of John Lennon’s “Oh my love” or of Henry Purcell’s much loved “Ô Solitude” are simply heart-stopping.

And the “chamber folk” treatment of such diverse songs as Tom Waits’ “All the world is green”, of “Ya Laure Hobouki” (a song composed for Lebanese singer Fairuz by the Rahbani brothers in the 1950s and recently covered in 2008 by Natasha Atlas) or of the Latin-American lullaby “Duerme Negrito” popularised by Argentine singer Atahualpa Yuapanqui is indicative of the scope and ambition of the project. Sung in French creole, “Sega Jacquot” is a wonderful homage to Luc Donat, the Sega musician and singer from the Réunion Island:

The CD also comes with a hardback booklet splendidly illustrated with a period painting for each song – the front cover itself is adapted from “Dors mon enfant” (Sleep my child), a 1788 picture by French painter Marguerite Gérard (1761 – 1837).

Birds on a Wire was released on 31st March 2014 last on Moriarty’s own label Air Rytmo. Birds on a Wire‘s album Ramages was released on 28 February 2020 last

English Translation by Frenchlations

You’re beautiful,

You’re beautiful because you’re brave

To look deep into the eyes

Of the one who challenges you to be happy

You’re beautiful,

You’re beautiful as a silent scream,

Strong as a precious metal,

who fights to heal its bruises,

It is like an old tune,

A few notes in torment,

That force my heart,

That force my joy,

When I think of you,

Now.

It is no good,

It is no good saying to myself that it is better this way,

Even if it still hurts,

I don’t have any silent refuge.

It is beautiful,

It is beautiful because it is stormy,

With this weather I know very little,

The words that stay at the corner of my eyes.

It is like an old tune,

A few notes in torment,

That force my heart,

That force my joy,

When I think of you.

You, you’re leaving the stage

Without a weapon and without hatred

I’m afraid to forget,

I’m afraid to accept,

I’m afraid of the living,

Now.

You’re beautiful…

More than 80 years after D-Day, the recipes and ingredients introduced during France’s wartime occupation are slowly making a comeback.

By June 1940, German forces had blitzed through France in just six weeks, leading more than half of the country to be occupied. As a result, French staples like cheese, bread and meat were soon rationed, and by 1942 some citizens were living on as few as 1,110 calories per day. Even after World War Two ended in 1945, access to food in France would continue to be regulated by the government until 1949.

Such austerity certainly had an impact on how the French ate during and just after the war. Yet, more than 80 years after Allied forces landed in Normandy to begin liberating the nation on D-Day (6 June 1944), few visitors realise that France’s wartime occupation still echoes across the nation’s culinary landscape.

In the decades following WW2, the French abandoned the staples that had got them through the tough times of occupation; familiar ingredients like root vegetables and even hearty pain de campagne (country bread) were so eschewed they were nearly forgotten. But as wartime associations have slowly faded from memory, a bevy of younger chefs and tastemakers are reviving the foods that once kept the French alive.

There aren’t many French residents old enough to vividly recall life in wartime France today, and fewer still would deign to discuss it. Author Kitty Morse only discovered her great-grandparents’ “Occupation diary and recipe book” after her own mother’s death. Morse released them in 2022 in her book Bitter Sweet: A Wartime Journal and Heirloom Recipes from Occupied France.

“My mother never said any of this to me,” she said.

Aline Pla was just nine years old in 1945 but, raised by small-town grocers in the south of France, she remembers more than others might. “You were only allowed a few grams of bread a day,” she recalled. “Some [people] stopped smoking – especially those with kids. They preferred trading for food.”

Such widespread lack gave rise to ersatz replacements: saccharine stood in for sugar; butter was supplanted by lard or margarine; and instead of coffee, people brewed roots or grains, like acorns, chickpeas or the barley Pla recalls villagers roasting at home. While many of these wartime brews faded from fashion, chicory coffee remained a staple, at least in northern France. Ricoré – a blend of chicory and instant coffee – has been on supermarket shelves since the 1950s. More recently, brands like Cherico are reimagining it for a new generation, marketing it as a climate-conscious, healthful alternative traditional coffee.

According to Patrick Rambourg, French culinary historian and author of Histoire de la Cuisine et de la Gastronomie Françaises, if chicory never wholly disappeared in France, it’s in large part thanks to its flavour. “Chicory tastes good,” he explained. “It doesn’t necessarily make you think of periods of austerity.”

Other products did, however, such as swedes and Jerusalem artichokes, which WW2 historian Fabrice Grenard asserted “were more reserved for animals before the war.” The French were nevertheless forced to rely heavily on them once potato rationing began in November 1940, and after the war, these vegetables became almost “taboo”, according to Rambourg. “My mother never cooked a swede in her life,” added Morse.

Two generations later, however, Jerusalem artichokes, in particular, have surged to near-omnipresence in Paris, from the trendy small plates at Belleville wine bar Paloma to the classic chalkboard menu at bistro Le Bon Georges. Alongside parsnips, turnips and swedes, they’re often self-awarely called “les legumes oubliés“(“the forgotten vegetables”) and, according to Léo Giorgis, chef-owner of L’Almanach Montmartre, French chefs have been remembering them for about 15 years.

“Now you see Jerusalem artichokes everywhere, [as well as] swedes [and] golden turnips,” he said. As a chef dedicated to seasonal produce, Giorgis finds their return inspiring, especially in winter. “Without them, we’re kind of stuck with cabbages and butternut squash.”

According to Apollonia Poilâne, the third generation of her family to run the eponymous bakery Poilâne, founded in 1932, a similar shift took place with French bread. Before the war, she explained, white baguettes, which weren’t subject to the same imposed prices as sourdough, surged to popularity on a marketplace rife with competition. But in August 1940, bread was one of the first products to be rationed, and soon, white bread was supplanted by darker-crumbed iterations bulked out with bran, chestnut, potato or buckwheat. The sale of fresh bread was forbidden by law, which some say was implemented specifically to reduce bread’s palatability.

“I never knew white bread!” said Pla. When one went to eat at a friend’s home during wartime, she recalled, “You brought your bread – your bread ration. Your own piece of bread.”

Hunger for white bread surged post-war – so much so that while Poilâne’s founder, Pierre Poilâne, persisted in producing the sourdoughs he so loved, his refusal to bake more modern loaves saw him ejected from bakery syndicates, according to his granddaughter, Apollonia. These days, however, the trend has come full circle: Baguette consumption fell 25% from 2015 to 2025, but the popularity of so-called “special” breads made with whole or heirloom grains is on the rise. “It’s not bad that we’re getting back to breads that are a bit less white,” said Pla.

For Grenard, however, the most lasting impact the war left on French food culture was a no-waste mindset. “What remains after the war is more of a state of mind than culinary practices,” he said. Rambourg agreed: “You know the value of food when you don’t have any.” Continue reading “How World War Two changed how France eats”