Category: Arts

Doisneau: Lunch on Champs Elysées

CHAQUE JOUR UNE NOUVELLE PHOTO DE ROBERT DOISNEAU [1959]

Le repas des travailleurs de la chaussée

Champs Elysées

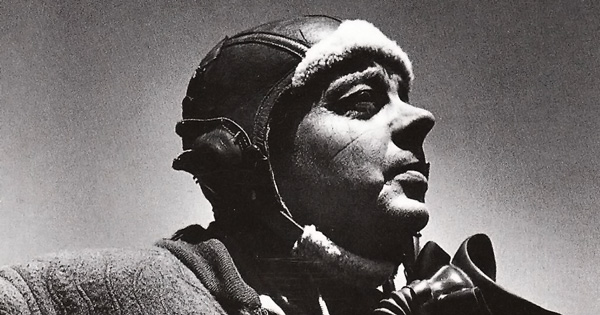

“Little Prince” Author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry on How a Simple Human Smile Saved His Life

“Care granted to the sick, welcome offered to the banished, forgiveness itself are worth nothing without a smile enlightening the deed.”

By Maria Popova

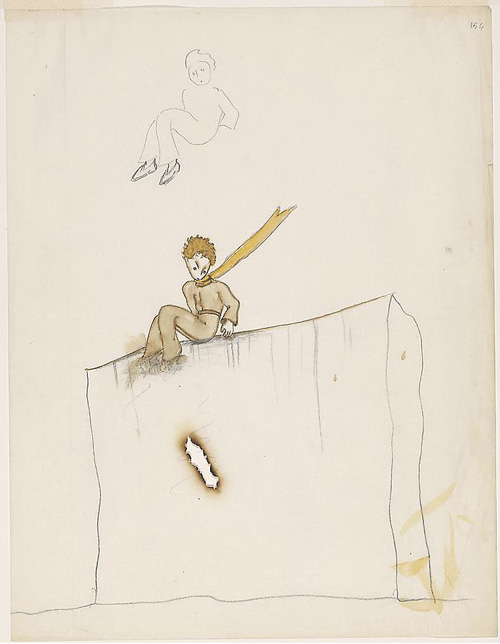

Though researchers since Darwin may have spent considerable effort on the science of smiles, at the heart of that simple human expression remains a metaphysical art — one captured nowhere more beautifully and grippingly than in a short account by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (June 29, 1900–July 31, 1944), found in Letter to a Hostage (public library) — the same exquisite short memoir he began writing in December of 1940, a little more than two years before he created The Little Prince on American soil, which also gave us his poignant reflection on what the Sahara desert teaches us about the meaning of life.Source: “Little Prince” Author Antoine de Saint-Exupéry on How a Simple Human Smile Saved His Life – The Marginalian

In a creative sandbox for what would become Saint-Exupéry’s most famous line in The Little Prince — “What is essential is invisible to the eye.” — he writes:

How does life construct those lines of force which make us alive?

[…]

Real miracles make little noise! Essential events are so simple!

One such essential event in Saint-Exupéry’s life had to do with the mundane miracle of a simple smile, a gift he so poetically describes as “a certain miracle of the sun, which had taken so much trouble, for so many million years, to achieve, through ourselves, that quality of a smile which was pure success.” He once again channels the spirit of his famous Little Prince line and writes:

The essential, most often, has no weight. The essential there, was apparently nothing but a smile. A smile is often the essential. One is paid with a smile. One is rewarded by a smile. And the quality of a smile might make one die.

Indeed, in a subsequent chapter, Saint-Exupéry recounts an incident that rendered a smile very much the difference between life and death — his life and death. One night during his time in Spain as a journalist reporting on the Civil War, he found himself with several revolver barrels pressed tightly into his stomach — the militia of the rebel forces had snuck up on him under the veil of the dark and captured him in “solemn silence,” staring at his tie — “such a luxury was not fashionable in an anarchist area” — rather than his face. He recounts:

My skin tightened. I waited for the shot, for this was the time of quick trials. But there was no shot. After a complete blank of a few seconds, during which the shifts at work appeared to dance in another universe — a kind of dream ballet — my anarchists, slightly nodding their heads, bid me precede them, and we set off, without hurry, across the lines of junction. The capture had been done in perfect silence, with an extraordinary economy of movement. It was like a game of creatures of the ocean bed.

I soon descended to a basement transformed into a guard post. Badly lit by a poor oil lamp, some other militia were dozing, their guns between their legs. They exchanged a few words, in a neutral voice, with the men of my patrol. One of them searched me.

Saint-Exupéry didn’t speak Spanish, but he understood enough Catalan to gather that his identity documents were being requested. He tried to communicate to his captors that he had left them at the hotel, that he was journalist, but they merely passed around his camera, yawning and expressionless. The atmosphere, to his surprise, wasn’t what one would expect of an anarchist militia camp:

The dominant impression was that of boredom. Boredom and sleep. The power of concentration of these men seemed exhausted. I almost wished for a sign of hostility, as a human contact. But … they gazed at me without any reaction, as if they were looking at a Chinese fish in an aquarium.

(One has to wonder whether that desire for contact, whatever its nature or cost, might be a universality of the human condition — the same impulse that drives trolls to spew the venom of hostility as a desperate antidote to their own apathy and existential boredom. Aggression is, perhaps, the only form of contact of which they are capable, and yet it is contact they crave so compulsively.)

After a tortuous period of observing his captors wait for nothing in particular, Saint-Exupéry grew increasingly exasperated with a longing for contact, for the mere acknowledgement of his existence. He paints the backdrop of the miracle that would take place:

In order to load myself with the weight of real presence, I felt a strange need to cry out something about myself, which would impose upon them the truth of my existence — my age for instance! That is impressive, the age of a man! That summarizes all his life. This maturity of his has taken a long time to achieve. It was grown through so many obstacles conquered, so many serious illnesses cured, so many griefs appeased, so many despairs overcome, so many dangers unconsciously passed. It has grown through so many desires, so many hopes, so many regrets, so many lapses, so much love. The age of a man, that represents a good load of experience and memories. In spite of decoys, jolts, and ruts, you have continued to plod like a horse drawing a cart.

Saint-Exupéry was thirty-seven at the time.

But what happened next had nothing to do with the achievement of age, or the gravitas of maturity, or any other willful self-assertion. Instead, it was driven by the simplest, most profound form of shared humanity:

Then the miracle happened. Oh! a very discreet miracle. I had no cigarette. As one of my guards was smoking, I asked him, by gesture, showing the vestige of a smile, if he would give me one. The man first stretched himself, slowly passed his hand across his brow, raised his eyes, no longer to my tie but to my face, and, to my great astonishment, he also attempted a smile. It was like the dawning of the day.

This miracle did not conclude the tragedy, it removed it altogether, as light does shadow. There had been no tragedy. This miracle altered nothing visible. The feeble oil lamp, the table scattered with papers, the men propped against the wall, the colors, the smell, everything remained unchanged. Yet everything was transformed in its very substance. That smile saved me. It was a sign just as final, as obvious in its future consequences, as unchangeable as the rising of the sun. It marked the beginning of a new era. Nothing had changed, everything was changed. The table scattered with papers became alive. The oil lamp became alive. The walls were alive. The boredom dripping from every lifeless thing in that cellar grew lighter as if by magic. It seemed that an invisible stream of blood had started flowing again, connecting all things in the same body, and restoring to them their significance.

The men had not moved either, but, though a minute earlier they had seemed to be farther away from me than an antediluvian species, now they grew into contemporary life. I had an extraordinary feeling of presence. That is it: of presence. And I was aware of a connection.

The boy who had smiled at me, and who, until a few minutes before, had been nothing but a function, a tool, a kind of monstrous insect, appeared now rather awkward, almost shy, of a wonderful shyness — that terrorist! He was no less a brute than any other. But the revelation of the man in him shed such a light upon his vulnerable side! We men assume haughty airs, but within the depth of our hearts, we know hesitation, doubt, grief.

Nothing had yet been said. Yet everything was resolved.

Saint-Exupéry ends with a reflection on the sacred universality and life-giving force of that one simple gesture, the human smile:

Care granted to the sick, welcome offered to the banished, forgiveness itself are worth nothing without a smile enlightening the deed. We communicate in a smile beyond languages, classes, and parties. We are faithful members of the same church, you with your customs, I with mine.

Four years after he wrote Letter to a Hostage, which is a sublime read in its totality, Saint-Exupéry disappeared over the Bay of Biscay never to return. Popular legend has it that Horst Rippert, the German fighter pilot who shot down the author’s plane, broke down and wept upon hearing the news — Saint-Exupéry had been his favorite author. What a tragic form of contact, war.

Isabella Rossellini

Matthew Rolston

Isabella Rossellini with Bird 1988

Piaf

Édith Piaf photographiée par Gjon Mili, 1946

Bardot being Bardot