That a pigeon-headed man is better suited to water than to ice is hardly something that most readers will feel requires no explanation, but Vian isn’t interested in explaining what he sees. He deploys his effects with deadpan bravado, as if they were nothing out of the ordinary. He works in a universe of pure lightness, rising up against what Italo Calvino once called “the weight, the inertia, the opacity of the world,” lifting himself above all laws of gravity out of a certainty that they do not apply to him.

Until, suddenly, they do. For most of the book, Colin and Chick live in a childish world, of girls and jazz and fun, but around them Vian’s surreal sketchbook starts to display an almost giddy cruelty. Vian evokes a mechanized world in which human lives, apart from those of the main characters, seem utterly expendable. At Partre’s lecture, his fans are so crazy to see him that some try to parachute in (a team of firefighters drown them with hoses) and others try to enter the hall through the sewers (security stomps them, and rats eat the survivors).

“Foam of the Days” is a deeply silly piece of work, but, as these macabre flourishes accumulate, it becomes, ultimately, a tragedy, following a descent into despair that is characteristic of Vian’s novels. Soon after her wedding, Chloe falls sick. A water lily is found growing in her lung, and her illness destroys Colin’s world, forcing him into the domain of money and misery and heaviness. Vian’s delight in youth and his sense of its fragility are always intertwined: it is the responsible lives of adults that are nonsensical, and a refusal to grow up that is the only reasonable way to live, but this natural course of things is not allowed. Like Vian, Colin wants nothing more than to play lovely games his whole life, but life will not let him.

“Foam of the Days” was the third novel that Vian wrote, but commercial success eluded him. In the summer of 1946, however, he made a wager with the head of a struggling publishing house that, given a few weeks, he could produce a best-seller. He sequestered himself for the next fifteen days, emerging to announce that he had discovered and translated a novel by an African-American writer named Vernon Sullivan, who had found no American publisher willing to touch it. The book, titled “I Spit on Your Graves,” is a pulpy, grotesque cartoon with a deliberately incendiary plot: a black man, passing for white, murders a pair of wealthy white girls he has seduced after his brother is lynched. Published in French toward the end of 1946, the book initially attracted only minimal notice, until a man named Daniel Parker, the leader of a right-wing morality watchdog group, Cartel d’Action Sociale et Morale, set out to have the book banned and its author, translator, and publisher prosecuted. The book’s notoriety increased further when a deranged man strangled his lover in a hotel room, and the police found a copy of the book by the bed. Passages in which the protagonist strangles a woman had been circled.

Riding on this tide of scandal, “I Spit on Your Graves” became the best-selling book in France in 1947. Amid the uproar, Vian maintained that he was merely the translator—he even published a text of the putative English original—but by the end of 1948 he had to admit that there was no Sullivan, and that he was the book’s sole author; he was eventually fined a hundred thousand francs for his offense to public morals. By then, a new Sullivan novel had appeared, “The Dead All Have the Same Skin,” the story of a white man so repulsed by the fear that he is black that he turns to murder and rape. Vian named him Dan Parker.

The Sullivan novels catapulted Vian to a sudden professional success, but, as he himself acknowledged, they are not very good. They are avowedly trashy, presumably influenced by Vian’s reading of American noir—an influence perhaps comparable to the effect of Hollywood B movies on French postwar cinema. Nonetheless, James Baldwin, in his long essay “The Devil Finds Work,” thought “I Spit on Your Graves” worth taking seriously: “What informs Vian’s book . . . is not sexual fantasy, but rage and pain: that rage and pain which Vian (almost alone) was able to hear in the black American musicians, in the bars, dives, and cellars, of the Paris of those years. . . . Vian would have known something of this from Faulkner, and from Richard Wright, and from Chester Himes, but he heard it in the music, and, indeed, he saw it in the streets.” Baldwin also observed that the book’s “vogue was due partly to the fact that it was presented as Vian’s translation of an American novel. But this vogue was due also to Vian himself, who was one of the most striking figures of a long-ago Saint-Germain des Prés.”

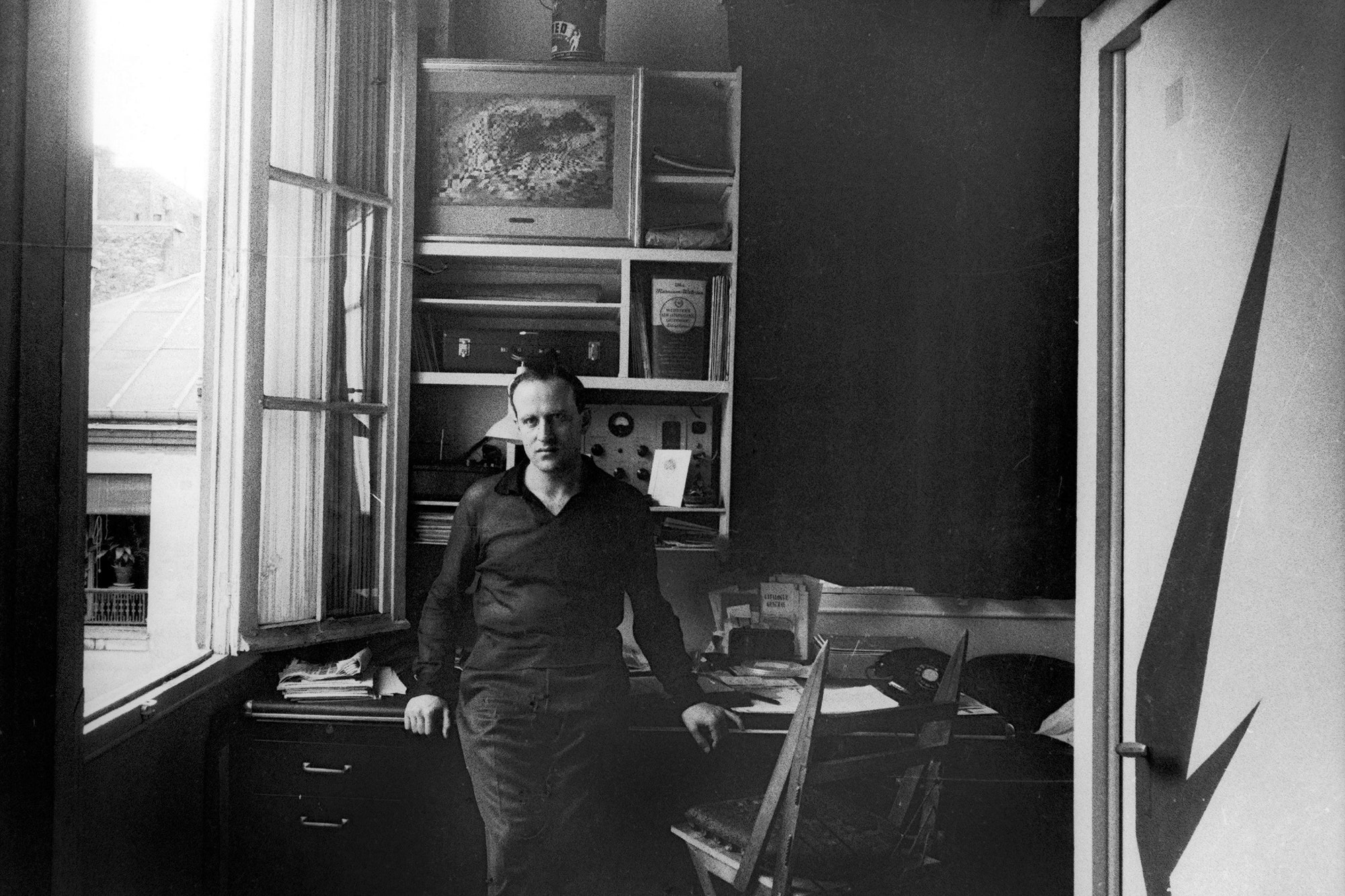

Indeed, from the end of the war, Vian was everywhere you looked—“the Prince of a subterranean kingdom,” his biographer Noël Arnaud called him, “a prince in shirtsleeves with a trumpet for his scepter.” “The Manual of Saint-Germain-des-Prés” portrays a scene filled with poets and painters, movie stars, singers, and philosophers—Jean Cocteau, Jean Genet, Alberto Giacometti, Tristan Tzara, Juliette Gréco, Simone Signoret. De Beauvoir, describing a party at the Vians’, recalled:

When I arrived, everyone had already drunk too much; his wife, Michelle, her long white silk hair falling on her shoulders, was smiling to the angels; Astruc . . . was sleeping on the sofa, shoeless; I also drank valiantly while listening to records imported from America. Around two in the morning Boris offered me a cup of coffee; we sat in the kitchen and until dawn we talked: about his novel, on jazz, on literature, about his profession as an engineer. I found no affectation in his long, white and smooth face, only an extreme gentleness and a kind of stubborn candor. . . . We spoke, and dawn arrived only too quickly. I had the highest appreciation, when I had the chance of enjoying them, for these fleeting moments of eternal friendship.

American culture, discouraged in France by the Vichy regime, held enormous attraction for the postwar generation, and arguably helped France reshape its sense of self after the shame of the Occupation. Vian was at the center of this movement. He wrote a vast amount of jazz criticism, most of it for a journal called Jazz Hot, a publication that was, to the music of the time, something like what Cahiers du Cinéma was, later, to film. He became a leading promoter of American jazz in France, helping organize Paris gigs for Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis, and taking visiting musicians to parties, restaurants, and clubs.

He also wrote three more novels as Sullivan and three under his own name, but nothing sold as well as “I Spit on Your Graves,” and, with each failure, Vian’s finances became shakier. His marriage ended, and so did the novels; his entire corpus of fiction was produced in an extraordinary burst of activity between 1946 and 1953. He kept himself busy, however, turning his attention to music, journalism, the theatre, and translations. His collected works, published recently in France, run to fifteen large volumes—six novels under his own name and four under the Sullivan pseudonym, as well as a torrent of plays, poems, short stories, film scripts, opera librettos, cabaret shows, essays, criticism, treatises, pornography, and hundreds of songs. He published writings under twenty-seven different pseudonyms, and translated a great deal of American fiction, including works by Richard Wright, Raymond Chandler, and Ray Bradbury.

Even as his health declined, through the nineteen-fifties, he showed a willingness, indeed a compulsion, to turn his talents to anything. He recorded many of his own songs, and, in 1954, his music restored him to notoriety, when “The Deserter”—an antiwar song written just before France’s defeat in Indochina and on the brink of the French-Algerian war—was banned. He also acted in six movies, most notably in Roger Vadim’s film version of “Les Liaisons Dangereuses.” He rounded out his career as a jazz A. & R. man, first for Philips and then for his friend the record producer Eddie Barclay.