For a long time, a sector of the Church directed and financed from the US attempted to depose the Vatican leader in order to impose its own identity-based ideology

By Daniel Verdu

On the morning of August 26, 2018, while the Pope was visiting Ireland with the usual entourage of journalists and Vatican staff, the bomb dropped. Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, a former Vatican envoy in Washington between 2011 and 2016 and a heavyweight within the Curia, accused the Pontiff in an 11-page letter of having covered up the abuses of Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, and demanded his resignation. The violent tone of that letter and the accusations it contained were the culmination of a campaign that had begun a few years earlier within the Holy See to overthrow a Pope they considered too progressive, a heretic even. The attempted schism was directed and financed from the United States, where Donald Trump was spending his first term in the White House and in search of a cultural and ideological narrative capable of flourishing on the Judeo-Christian roots of the Western world. And the Vatican, from that perspective, could not be governed by a Pope who was an environmentalist, tolerant of homosexuality, an anti-capitalist, and, above all, extremely belligerent toward the anti-immigration policies that characterized Trump’s first presidency.

There have always been tensions and internal struggles in the history of the Roman Catholic Church. Unity and avoiding schism were an obsession. But never in contemporary history had a Pope been so violently targeted. And, above all, it was completely unusual for the Pontiff’s enemies to come from the traditionalist sector, supposedly the keeper of the essence of Catholicism. Until then, such battles had been fought only by far-right groups like the Society of St. Pius X, founded by the rebel French archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, who was excommunicated in 1988 after ordaining four priests without Rome’s permission.

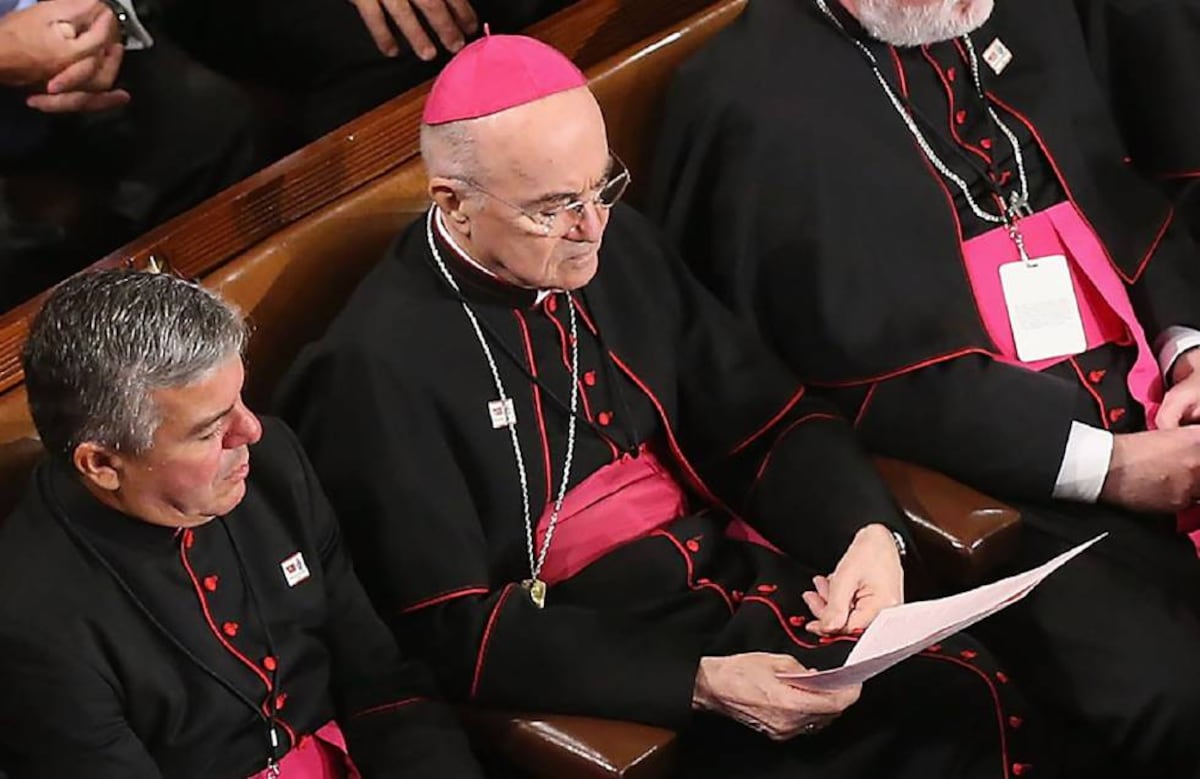

The symptoms had been clear for some time. Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s chief advisor before his fall from grace, a sort of Elon Musk avant la lettre, settled into the penthouse of the Hotel De Russie on the luxurious Via del Babuino. From there, he began receiving Italian and European leaders who viewed the Pope unfavorably: from Matteo Salvini to Trump himself. Bannon attempted to open a sort of school of populism on the outskirts of Rome, increasing the pressure through sympathetic media. The American Cardinal Raymond Burke became the political arm of this new movement within the Vatican, and together with other cardinals such as the excellent theologian Gerhard Müller, they began to hatch a plan to expose Francis’s alleged lack of intellectual preparation.

“It began early, in the summer of 2013, when it was already clear that many U.S. bishops didn’t recognize him as one of their own,” notes Massimo Faggioli, a professor in the department of theology and religious sciences at Villanova University in Philadelphia. “American conservatives thought that after John Paul II and Benedict XVI, their destiny was forever marked by neoconservatism. And the Pope didn’t allow it. That was his sin,” he adds.

In the United States, there are approximately 72.3 million baptized people, almost a quarter of the population. But the influence of Catholics has grown in recent years. A third of the members of Congress practice that faith, according to a study by the Pew Research Center. Vocations to one of the richest churches in the world have fallen more than anywhere else, and pedophilia scandals, with the now-famous Boston case, wreaked havoc. However, the obsession with the Vatican of the new White House occupants and neoconservative power circles has continued to grow.

One of the impressions that always haunted Bergoglio was that Benedict XVI’s resignation in 2013, despite having been a gesture of generosity and humility, had opened a rift in the Church that the conservative sector seized upon to wage its struggle. The fiction that was established was that if there were two men dressed in white strolling through the Vatican gardens, why not close ranks around the more conservative one? Ratzinger, an excellent theologian, though not skilled in personal relationships, never accepted that role. But some oversights and the influence of his personal secretary, Georg Gänswein, who was at odds with Francis, caused some slip-ups.

The height of tension came five years ago with the publication of a book that the Pope Emeritus was supposedly co-authoring with the ultra-conservative Cardinal Robert Sarah, in which he strongly opposed optional celibacy and, above all, the ordination of married men (From the Depths of Our Hearts). This was an issue on which Francis was due to address the synod on the Amazon, and which turned the publication into an act of interference.

Francis kept up the fight to the bitter end. On February 10, in fact, he sent a letter to the U.S. bishops (195 dioceses) denouncing the Trump administration’s program of mass deportations. The letter infuriated Tom Homan, known as the border czar. “He has a wall around the Vatican, does he not? I wish he’d stick to the Catholic Church and fix that and leave border enforcement to us,” he replied. “He never let himself be intimidated. He responded all those years with appointments, trips, documents. And the things he didn’t do, like the appointment of female priests, it was because he didn’t believe in it,” Faggioli argues.

The Joe Biden administration provided temporary relief, but the American Church itself was already deeply divided. “These are cultural and social universes that have grown in a different way. It’s a Catholicism that is more based on identity. That’s why we now find ourselves at a critical point with this conclave. There is a neoconservative movement that began in the 1980s. And the Vice President of the United States, J. D. Vance, is one of its exponents. They have a long-term strategy to return to a certain traditionalism that will not end with the conclave, no matter what.” In an ironic twist of fate, perhaps his way of dealing with this struggle, Francis dedicated part of his last day on this Earth to receiving Vance at the Vatican.