Crossing Brooklyn Ferry

“I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself or be understood.”

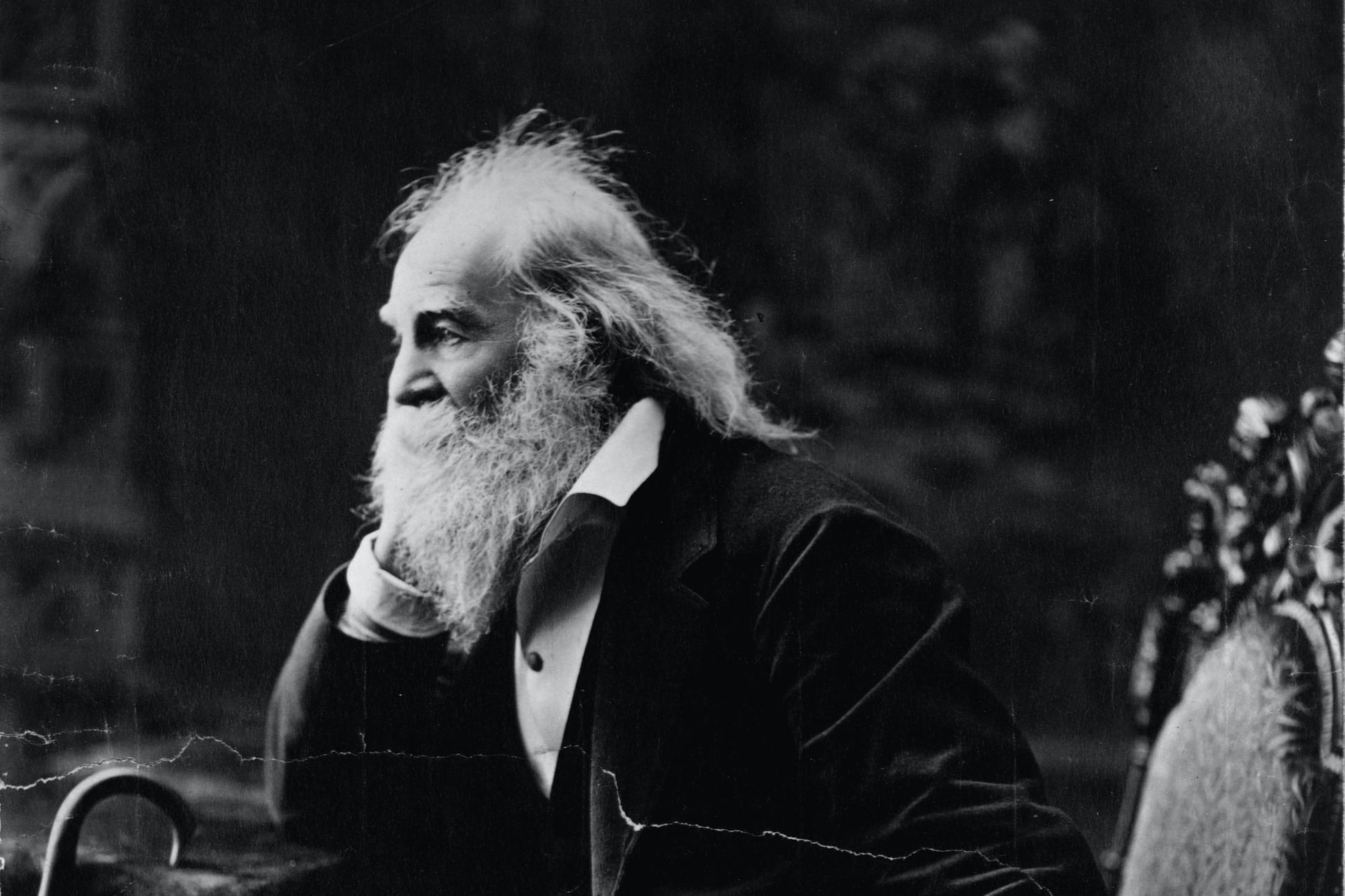

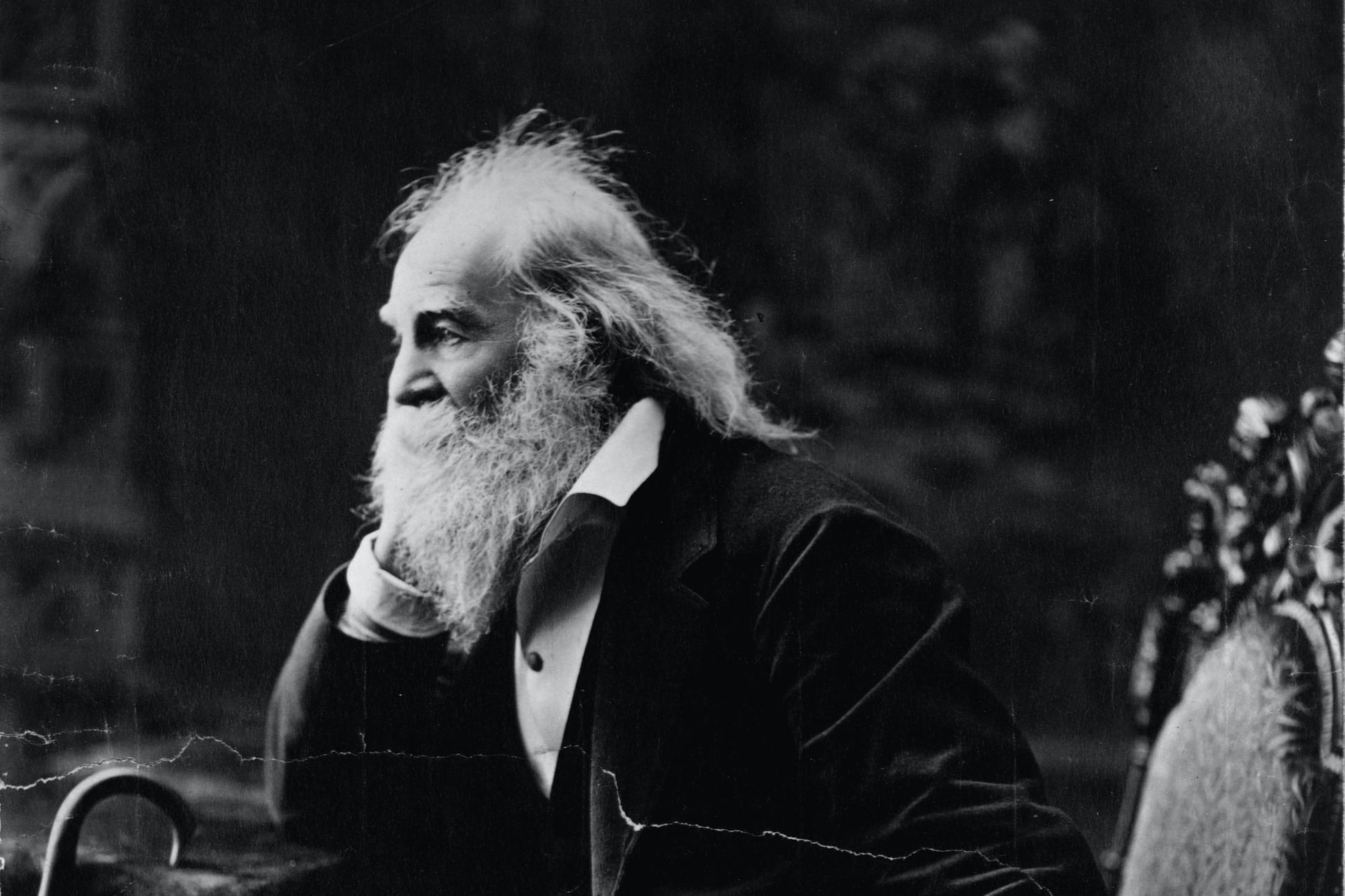

Re-examine all you have been told at school or church or in any book, dismiss whatever insults your own soul,” Walt Whitman (May 31, 1819–March 26, 1892) wrote in offering his timeless advice on living a vibrant and rewarding life in the preface to Leaves of Grass. When Whitman first published his masterpiece in 1855, it was met with indifference punctuated by bursts of harsh criticism. It is difficult to imagine just how insulting to the young poet’s soul such reception must have been, or what it took for him to dismiss it and carry on writing. What buoyed his spirit through the tidal wave of negativity was an extraordinary letter of appreciation from Ralph Waldo Emerson — the era’s most respected literary tastemaker and Whitman’s greatest hero, whose 1844 essay The Poet had inspired Leaves of Grass. The young poet wore Emerson’s praise of “incomparable things said incomparably well” like an armor, almost literally — he carried the letter folded in his shirt-pocket over his heart, regularly reading it to friends and lovers.

It is certainly easier, though never easy, to dismiss what insults one’s soul when it comes from critics who haven’t earned one’s confidence — “Take no notice of anyone you don’t respect,” Jeanette Winterson offered in her ten wise rules of writing. But to dismiss criticism that insults the soul from someone we respect — or, harder still, love — requires superhuman strength of spirit. How do we hold on to the integrity and solidity of our conviction and vision, be it creative or existential, when it is being challenged and censured by a person we regard with high intellectual esteem and tenderness of heart?

Whitman modeled this exquisitely in an encounter with Emerson himself.

On a crisp February afternoon in 1860, five years after the publication of Leaves of Grass, the two men took a two-hour walk along Boston Common. They had by then befriended one another and formed a courteous, frank relationship embodying Emerson’s ideal of friendship: “A friend is a person with whom I may be sincere.” That winter day, Whitman found Emerson to be “in his prime, keen, physically and morally magnetic, arm’d at every point, and when he chose, wielding the emotional just as well as the intellectual.” When the criticism came, Whitman knew it sprang from that selfsame source — a quality of character he deeply respected, even revered. And yet, rather than coming undone by self-doubt, he was able to stay rooted in his own values and vision.

Writing in Specimen Days (public library) — the endlessly rewarding collection of prose fragments and diary entries, which gave us Whitman on the wisdom of trees, the power of music, the essence of happiness, the “meaning” of art, and optimism as a force of resistance — he recounts:

During those two hours he was the talker and I the listener. It was an argumentstatement, reconnoitring, review, attack, and pressing home, (like an army corps in order, artillery, cavalry, infantry,) of all that could be said against that part (and a main part) in the construction of my poems, “Children of Adam.” More precious than gold to me that dissertation — it afforded me, ever after, this strange and paradoxical lesson; each point of E.’s statement was unanswerable, no judge’s charge ever more complete or convincing, I could never hear the points better put — and then I felt down in my soul the clear and unmistakable conviction to disobey all, and pursue my own way. “What have you to say then to such things?” said E., pausing in conclusion. “Only that while I can’t answer them at all, I feel more settled than ever to adhere to my own theory, and exemplify it,” was my candid response. Whereupon we went and had a good dinner at the American House. And thenceforward I never waver’d or was touch’d with qualms, (as I confess I had been two or three times before).

Emerson — the patron saint of self-reliance, who exhorted: “Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.” — no doubt appreciated this orientation of spirit. Whitman’s first and foremost biographer, the great naturalist John Burroughs, goes even further in his sublimely poetic 1896 biography Whitman: A Study:

In many ways was Whitman, quite unconsciously to himself, the man Emerson invoked and prayed for — the absolutely self-reliant man; the man who should find his own day and land sufficient; who had no desire to be Greek, or Italian, or French, or English, but only himself; who should not whine, or apologize, or go abroad; who should not duck, or deprecate, or borrow; and who could see through the many disguises and debasements of our times the lineaments of the same gods that so ravished the bards of old.

To be sure, Whitman did not dismiss criticism wholesale — rather, he separated the wheat from the chaff through the sieve of confidence and surefooted creative vision. But criticism, he believed, could be far more valuable than praise. In Leaves of Grass, he wrote under the heading “STRONGER LESSONS”:

Have you learn’d lessons only of those who admired you and were tender with you? and stood aside for you?

Have you not learn’d great lessons from those who reject you, and brace themselves against you? or who treat you with contempt, or dispute the passage with you?

The kind of criticism he readily dismissed was that of the professional critics and opinionators — those aimed at tearing down rather than improving a writer’s art, for their judgments are based on the standards of their time and therefore tend to censure any vigorous break with convention. Such critics are apt to pronounce any work of true originality bad, and then to embody W.H. Auden’s incisive observation that “one cannot review a bad book without showing off.”

Burroughs noted this in his praiseful biography of Whitman, composed at a time when the poet was still more rejected than celebrated by his era:

There are no more precious and tonic pages in history than the records of men who have faced unpopularity, odium, hatred, ridicule, detraction, in obedience to an inward voice, and never lost courage or good-nature.

[…]

Every man is a partaker in the triumph of him who is always true to himself and makes no compromises with customs, schools, or opinions.

Whitman himself had proclaimed in Leaves of Grass:

I do not trouble my spirit to vindicate itself or be understood.

Later in life, he would reflect:

Has it never occurr’d to any one how the last deciding tests applicable to a book are entirely outside of technical and grammatical ones, and that any truly first-class production has little or nothing to do with the rules and calibres of ordinary critics?… I have fancied the ocean and the daylight, the mountain and the forest, putting their spirit in a judgment on our books. I have fancied some disembodied human soul giving its verdict.

[…]

The quality of BEING, in the object’s self, according to its own central idea and purpose, and of growing therefrom and thereto — not criticism by other standards, and adjustments thereto — is the lesson of Nature.

Whitman’s poetry, founded upon the unshakable foundation of his creative and spiritual vision, eventually catapulted him to the top of the English-language literary pantheon. Leaves of Grass endures as one of the most beloved poetic works of all time, having influenced generations of writers and buoyed ordinary livers of life through the worst existential upheavals — such is the power of poetic truth channeled with unwavering stability of confidence and vision.

Complement with Descartes on the crucial difference between confidence and pride, Bruce Lee on willpower and self-esteem, and some excellent advice from great writers on how to survive criticism, then revisit Whitman on creativity, democracy, his advice to the young, and his most direct definition of happiness.